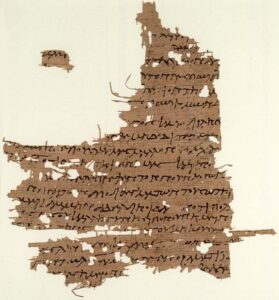

In the first few centuries after Jesus, there was an enormous variety of understandings of who He was, and what His life, death, and resurrection meant. On this topic quite a few contenders for the title of ‘sacred book’ were written and circulated, most of which didn’t make it into our official Bible. One of them is the Gospel of Mary. This week I’ll share the extraordinary story of how we come to have this document at all, and next week we’ll look at the text itself. About half of the Gospel of Mary has survived — it’s not looking good for the other half. It survives in three pieces: a longer Coptic copy from around the 5th century, and two small Greek fragments both dating from the 3rd century. Each has its own story.

The first piece to be found was the Coptic copy. (Coptic was the language of Egypt from about 300 CE to 800 CE, descended from the language of ancient Egypt.) In 1896 a manuscript dealer whose name history has forgotten offered a papyrus book for sale to a German scholar named Carl Reinhardt. Unbeknownst to either of them, it contained the Gospel of Mary along with three other previously unknown works: the Apocryphon of John, the Sophia of Jesus Christ, and the Act of Peter.

Reinhardt could tell that the book was ancient, but knew nothing more except that the dealer was from Achmim in central Egypt. The dealer said it had been found in the niche of a wall, but that’s unlikely as ancient papyrus doesn’t survive unless it is more or less hermetically sealed in a pot, in the ground and/or in a cave. Was it come by illegally, or perhaps recently found and placed in a niche in a wall? We’ll never know. Regardless, Reinhardt purchased the book and took it to Berlin, where it was placed in the Egyptian Museum and given its official title ‘Codex Berolinensis 8502’ (or the ‘Berlin Codex’ for short). There it came into the hands of Egyptologist Carl Schmidt (1868-1938), who set about producing a critical edition and German translation. (‘Critical edition’ means ‘super-scholarly’.)

From the beginning Schmidt’s efforts were plagued by difficulties. First all, it’s missing the first six pages, plus four pages from the middle. The manuscript itself was still inside its original cover made of feathers (!), leather and papyrus, but by the time it reached Schmidt the order of the pages had been considerably jumbled. (It certainly wasn’t created that way! What’s up with that?)

By 1912 Schmidt’s edition was ready for publication. But alas, the printer was near completion of the final sheets when a burst water pipe destroyed the entire edition. Soon after, Europe was plunged into World War I. During the war and its aftermath Schmidt was unable to go to Leipzig and salvage anything, but he did manage to resurrect the project anyway. This time he was thwarted in 1938 by his own mortality. His efforts were retrieved from his estate, and another scholar — Walter Till — took over shepherding the project through the publication process.

Meanwhile, in 1917 a small third-century Greek fragment was found in Egypt (its official designation is ‘Papyrus Rylands 463’). Till incorporated this new evidence into his edition, and by 1943 the edition was ready to go to press. But now World War II made publication impossible.

Meanwhile, there was the Nag Hammadi find in 1945: a collection of early Christian and Gnostic texts discovered near the Upper Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi. Till delayed publication to see if anything more of the Gospel of Mary was found in the Nag Hammadi texts. But sifting that library was a glacial process, and finally Till gave up waiting:

In the course of the twelve years during which I have labored over the texts, I often made repeated changes here and there, and that will probably continue to be the case. But at some point a man must find the courage to let the manuscript leave one’s hand, even if one is convinced that there is much that is still imperfect. That is unavoidable with all human endeavors.

— Walter Till

So, in 1955, the first printed edition of the text of the Gospel of Mary finally appeared with a German translation — nearly 60 years after Codex Berlin was found. (In a library near you!)

Meanwhile, yet another major find for ancient scholarship surfaced: the Oxyrhynchus Papyri. Oxyrhynchus was a thriving city in Egypt since the time of Alexander the Great, but after the Arab conquest in 641 CE its canal system (for supplying water from the Nile) fell into disrepair and the city was abandoned. Today all that remains are ruins — and its garbage dump. In the late 1800’s papyrologists Bernard Grenfell (1869-1926) and Arthur Hunt (1871-1934) thought they might excavate this dump and see what could be found. A lot, as it turns out — since 1898, scholars have assembled and transcribed over 5,000 documents from what were originally hundreds of boxes of papyrus fragments the size of large cornflakes. This is thought to represent only 1 to 2% of what is estimated to be at least half a million papyri still remaining to be conserved, transcribed, deciphered and catalogued. (The world’s largest jigsaw puzzle, with most of the pieces damaged or missing, and no picture on the box!)

Grenfell and Hunt devoted the rest of their lives working together on the Oxyrhynchus project — winters in Egypt when it was cool enough to excavate, summers in Oxford to sort out their finds. But theirs was not a happy end: In 1920 a third nervous breakdown ended Grenfell’s working life; Hunt went on until 1934, his last years clouded by the early death of his only son. But their efforts are continued by scholars today — the most recent volume was Vol. 85, published in 2020. (They publish a volume a year.)

Most of these papyri seem to be public and private documents: official correspondence, tax and court records, receipts, wills, inventories, horoscopes, private letters, and the like. All of which have given modern scholars an enormous window into day-to-day life in ancient times. But about 10% are literary in nature — and have included another fragment of the Gospel of Mary (Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 3525) dating from the early third century.

The fact that we have three fragments from differing locations suggests that the Gospel of Mary may have been widely circulated in its day.

Stories like these remind me of the unimaginable sweat and labor that previous generations have exerted (and monies spent) to bequeath to us even the smallest of treasures.

Suggested Reading

King, Karen; The Gospel of Mary of Magdala; Polebridge Press; Santa Rosa, CA; ISBN-13: 978-0944344583; Amazon